F8

Art

December 7, 2022

Chasing Provenance

Royalties, digital certificates, provenance. This is the language of modern smart contracts, and it’s being used to rewrite the rules of the art market as we know it.

Words by Charlotte Kent

Photos courtesy Various artists

The past few years of news stories, documentaries and court cases about forgeries and looted art have brought the importance of provenance to a wider audience. The purpose of provenance is not only to assure art audiences that the work was produced by the artist but also that the collector is the rightful owner. Blockchain technology offers to lessen the confusion surrounding authenticity by providing an immutable ledger to record the artwork’s history. It also enables visual artists to share in the profit of their works, sparking fresh debate about resale royalties.

The blockchain ledger can record information, but smart contracts are what enable resale royalties. Smart contracts — code that is executed automatically when certain conditions are met — were initially proposed in 1994 by Nick Szabo as a way of merging e-commerce and contract law using computer protocols that eliminated the need for human intervention. Fast-forward to 2018, and the arrival of ERC-721 on the Ethereum blockchain made possible a unique digital certificate of ownership for a virtual object.

Since digital objects can be posted and reposted, shared and right-click-saved online, the advent of ERC-721 revolutionized the potential of digital art to participate in the art world’s market of scarcity, with the smart contract specifying the sale terms. Blockchain’s record-keeping has also presented a way to publicly disclose a work’s ownership and transaction history. By extension, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have presented a radical opportunity, but the technology is not fail-proof and frequently reintroduces the need for social and legal contracts, which is precisely what the artist Nancy Baker Cahill showed in her work Contract Killers (2021).

Sarah Meyohas, Speculations - Bitchcoin

Contract Killers (Social), accompanying sculpture to Contract Killers NFT. © 2021 Nancy Baker Cahill. All Rights Reserved.

Blockchain’s New Contract

Contract Killers is an augmented-reality work that shows the disintegration of a handshake in front of three symbolic institutions: City Hall in Los Angeles, to represent the failures of civic agreements; the city’s Hall of Justice, to acknowledge judicial miscarriages; and a pile of money, to indicate the “gross inequities of late-stage capitalism.” A fourth hot-pink handshake in front of a gray wall represents the breakdown of social contracts.

The project uses blockchain not only to sell the individual works as NFTs but also to address the rhetoric about disintermediation and transparency surrounding the technology. Accompanying her own smart contract, Baker Cahill included a legal agreement ”intended to be readable and understandable by non-lawyer, NFT purchasers, so that there is no confusion as to intent, application, and scope of the terms.” This is just one of the ways Baker Cahill’s Contract Killers seeks to inject equity and openness into the opaque art market.

Blockchain’s claims to transparency are obviated by the fact that many NFT collectors can’t read code any more than they can understand a legal contract. To be clear: Smart contracts are neither smart nor contracts. They are neither as clearly automated as the word “smart” would suggest, nor are they legally binding contracts. For example, when an NFT is sold on a different platform than the one where it was minted, the automatic royalty doesn’t necessarily work. The claim that “code is law” is common in the blockchain; though it has been espoused since software became common at the turn of the century, the court cases that will determine to what degree that applies are just now emerging.

Though artists, collectors and dealers all want to cultivate trust and a sense of stewardship, articulating precise expectations around what stewardship entails has been rare. Blockchain smart contracts address the power imbalance where artists are expected to accept contracts, not produce them. Patrons in 15th-century Florence produced contracts stating in precise terms what they were funding; even the eccentric English surrealist Edward James had contractual agreements with the artists he supported, like René Magritte and Salvador Dalí.

Now, as artists design a smart contract, they are in a position to stipulate their own expectations, such as a percentage of future sales or a resale timeline. In so doing, they can circumvent the speculative transaction of “flipping,” where a work is bought and typically resold for profit at auction, spiking an artist’s market value in the short term and crippling their long-term growth. Still, smart contracts are dependent on social agreements.

And Baker Cahill’s point is that social dynamics cannot be coded. Blockchain’s premise of a trustless system dangerously ignores the ongoing realities of social relations that are integral to the art market. People buy art as an investment but also because they like it. Collectors frequently want to follow and engage the artist. Such relationships can be supported by legal agreements, but those depend on trust in society and its systems. Contract Killers cleverly uses blockchain to halt overexcited solutionism and insist on repairing our current systems, too.

Contract Killers (Judicial) augmented reality intervention in front of LA City Hall of Justice in 2021. © 2021 Nancy Baker Cahill. All Rights Reserved.

A Matter of Trust

An artwork’s provenance is partly established by verifying that it came from the artist’s studio or was handled by the artist. Verified provenance not only authenticates an artwork by establishing a historical record of past owners, but increases the work’s value by ensuring authenticity through a careful legacy. As the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) says in their Provenance Guide: “The object itself is the most important primary resource and a valuable source of provenance information.” Blockchain’s record of every transaction provides a provenance history, but how can that be ensured when the smart contract comes from the platform? How can the blockchain record be tied to a physical artifact?

The sculptor Hamzat Raheem has an answer. He deployed his own smart contract so that the NFTs he created could act as certificates of title clearly originating from him, just as his marble and plaster sculptures come from his studio, thereby ensuring a clear provenance. He tackles the matter in his project Creative Archaeology (2022), where collectors dig in soil to find one of his sculptures. These are embedded with a near-field communication (NFC) chip. When scanned on a mobile device, the chip activates a private webpage where the finder communicates their wallet address to the artist. Raheem can then send the smart contract that acts as the Certificate of Authenticated Title, developed with intellectual property and arts lawyer Megan Noh. The contract declares that the physical sculpture and certificate, represented by the NFT, must remain united. Transferring one without including the other mutilates the work, according to the contract.

Baker Cahill, Raheem and many other artists are using blockchain and smart contracts to inscribe a new set of social values around collecting art while including legacy practices like legal contracts to support their effort. The royalty approach itself is less important than establishing a relationship of mutual care between artist and collector. And the visual artifact becomes the object representing the importance of that trusting connection.

Media art is often celebrated for its interactivity, and these experimentations with smart contracts reveal blockchain’s ability to alter social relations. Since smart contracts are about encoding events between two parties, these artists push beyond the prescribed contracts of established platforms to explore the potential this technology offers for real social change.

Some galleries have been supportive of the creative prospects inherent to NFTs, especially those representing digital artists. For example, Bitforms Gallery and Postmasters worked with the white-label platform Monegraph to create their own NFT platforms with modifiable smart contracts. The gallerist Magda Sawon of Postmasters has been selling groundbreaking media art as well as physical works for 38 years, and she has recognized that artists are mobilizing blockchain for their creative practice. She and her partner launched PostmastersBC to support artists and collectors, who unlike Raheem may still be new to the technology and need support. The gallery educates the community on blockchain technology as a part of any creative or collecting endeavor. Many in the NFT space have disparaged galleries and curators as gatekeeping intermediaries in sale transactions, but gallerists argue that NFT platforms also charge commissions and “provide spectacularly limited service in maintenance of artwork and career management,” as Sawon decried in an emailed statement. Without that support, artists must marshal their own trajectory while remaining at the mercy of platform protocols.

When a group of crypto artists insisted in 2020 that NFT platforms establish and normalize 10% royalties on resales, the technology’s automation made it an easy ask; though the debate resurfaced when the trading platform Sudoswap didn’t include resale royalties, leading to loud objections by artists who’d already fought this fight. Reflecting on the Contract Killers project a year later, amid the sparring around royalties, Baker Cahill said, “Even standard protocols like that require baseline social agreements. That presumes centralized thought, which is counter to the idolatry of decentralization in the NFT ecosystem.” As the technology develops and expands its reach, differing views around the role of consensus are sure to occur. The flexibility of smart contracts is their creative potential, but their mobilization across cultures will reveal cracks in current social contracts.

Sarah Meyohas, Speculations - Bitchcoin

Sarah Meyohas, Speculations - Bitchcoin

Beyond Resale Royalties

The future of blockchain is evolving alongside the artists pushing its boundaries, most notoriously surrounding resale royalties. While actors, writers, graphic designers, and even software engineers have royalty norms in their industries, visual artists have long been disregarded. Blockchain came along and made possible what social and legal efforts had not.

Now artists are presented with a panoply of alternative funding practices beyond royalties. As companies like Masterworks buy art and fractionalize ownership across investors, market regulations and tax obligations appear; Masterworks files paperwork with the SEC before selling shares, an example of how established regulations expand and adapt to new systems. Artists using blockchain have been exploring these avenues since the technology appeared, and they exemplify the most interesting opportunities for long-term profit sharing in an artist’s work.

Simon de la Rouviere’s This Artwork Is Always On Sale (2019) operates according to a novel tax concept, the Common Ownership Self-Assessed Tax (COST) model. COST was conceived by Glen Weyl and Eric Posner in their book, Radical Markets (2018), as an alternative way to conceive of ownership while also enforcing a perpetual payment structure. De la Rouviere took this concept as an opportunity for digital artists to disrupt market practice. The owner of an object — the authors originally provided a case study in real estate — must always list their asking price, and the seller cannot refuse to sell at that price. The set price then becomes the basis for dividend disbursements overtime, which might be paid to an artist for a creative object. De la Rouviere minted and auctioned the conceptual work on March 21, 2019, with a patronage rate of 5%. A new version was created in 2020, and the artist has posted about how others can create their own version. Fractionalized ownership is receiving renewed interest as an opportunity for groups to pool funds and purchase costly goods, like high-end art. The artist Eve Sussman experimented with this formula in 89 Seconds Atomized (2018), a blockchain project based on her short film 89 Seconds at Alcázar (2004), itself inspired by Velásquez’s Las Meninas (1656).

Sussman produced 2,304 NFTs, each corresponding to an “atom” of the 10-minute media work. Though she retained 804 atoms, a full screening requires that all owners agree to contribute their atom at a specified time. Where Masterworks uses this model as an investment fund, artists can pool smaller collectors to support large-scale, or high-priced, projects.

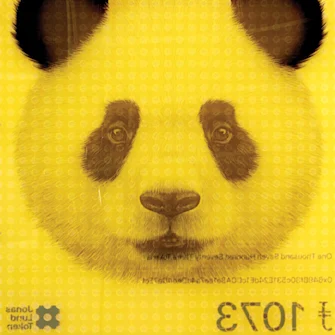

In February 2015, the artist Sarah Meyohas launched Bitchcoin, another model for group support. In her white paper, she explains that each Bitchcoin represents a 5-by-5-inch segment of one of her works. In the original launch, that meant photographs from her Speculations series, which were placed in a bank vault. Possession of 25 Bitchcoins, for a total price of $2,500, provided control over the 625 square inches of one photograph. The owner could then choose to access the physical photograph, or redeem the value for a future print, thereby encouraging collectors to become long-term investors in Meyohas’s work. Predating the launch of Ethereum (and its ability to automate aspects of shared ownership) by five months, Bitchcoin was an early exploration of how artists could finance their practice. The project’s legacy status has contributed to widespread respect for Meyohas, with a new release of Bitchcoins auctioned at Phillips in 2021, fetching up to 10 times the original price per unit.

Bitcoin represents an early form of what is now described as a social token. Particularly in the music and sports industries, social tokens enable celebrities to tap the support of their fans in order to distance themselves from the demands or limitations imposed by their representation. Creatives promise token owners access to certain events and opportunities, with the coin value increasing alongside the artist’s success. In visual art, these typically operate under the guise of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) that can act as trusts, LLCs and community projects; in the United States, the state of Wyoming allowed DAOs to register as LLCs as of July 1, 2021. With all members contributing to a shared wallet, a DAO becomes self-governing and self-regulating, automating the administration of the group. The encoded rules regarding member votes can mechanize certain functions, such as bidding on an artwork. Most DAOs have very active chat rooms where members participate in vigorous debate about any given issue.

“As the career path of Jonas Lund improves and his market value increases, so does the value of a Jonas Lund Token, thus allowing shareholders to profit through dividends and potential sales of the tokens,” states the website of Jonas Lund Token (JLT). JLT is a DAO with 100,000 tokens distributed among parties with voting rights and shared responsibility for the projects that Jonas Lund produces. An advisory board’s vested interest in the artist’s success provides strategy guidance, but all potential projects are presented to token holders, who discuss and vote on what work Lund will produce.

Blockchain is a technology in progress, not a monolithic structure, and artists can exploit its flexibility to remind audiences of its manifold prospects. Blockchain and smart contracts aren’t just impacting the digital sphere, but the breadth of the entire art market. “The idea of smart contracts may be giving artists in the legacy art world confidence to demand the inclusion of resale limitation rights in IRL transactions of physical works,” wrote Yayoi Shionori, arts lawyer and representative for the Chris Burden estate, reflecting on the impact of this emergent technology.

Certainly blockchain offers an opportunity to ensure provenance and reassure owners of the origin and authenticity of the works they purchase. But confidence in one’s artistic value, and the tools to claim it as well? That gift to an artist is beyond measure.

The Red Telephone, Jonas Lund Token (JLT) Helpline, 2020, auto-dialing telephone

Jonas Lund Token Proposal #23, 2019, UV Print on laser cut plexiglass, 100 x 80 x 4 cm, Courtesy of the Artist.