F5

Super Apps

Volume 1

The Great Super App Race

The true promise of the super app is creating a living digital economy – and charging everyone rent. Can anyone in the western world pull it off?

Words by Holden Bale

Photos courtesy Stocksy

In late 2010, a team of seven software engineers in China were given a project to create a mobile application for text messaging and photo sharing. They released the project in January of the next year, but a direct competitor – MiTalk – already had roughly 5 million users, and was focused on a similar premise.

A few months later, the team finished a new feature, inspired by the success of another app called TalkBox: the ability to record and send audio snippets. At the time, the experience of typing on mobile keyboards wasn’t designed with non-Roman alphabets in mind, and Pinyin – a system to transliterate Chinese to make it easier for users to text – was not yet widely adopted by older generations. Suddenly, the simplicity of sending short voice messages to friends and family became a ‘killer feature,’ causing downloads of the app to skyrocket.

Of course, those seven engineers worked for Tencent, one of China’s leading internet companies, and the new application was WeChat. When it launched, Tencent’s desktop messaging program QQ, akin to AOL Instant Messenger, had over 600 million active accounts. Today, WeChat has over one billion daily active users — more than the combined populations of the United States and the entire European Union. WeChat Pay, originally designed as a solution for managers at Tencent to give ‘red packet’ gifts to their employees in celebration of Chinese New Year, has more users than Apple Pay, and processes more than one billion transactions per day ranging from in-store shopping to consumers paying their utility bills. WeChat Work, with similar functionality to Slack and Microsoft Teams, has over 75 million users – more than six times the estimated number of users on Slack, which Salesforce acquired in 2021 for $27.7 billion.

Rise of the Super App

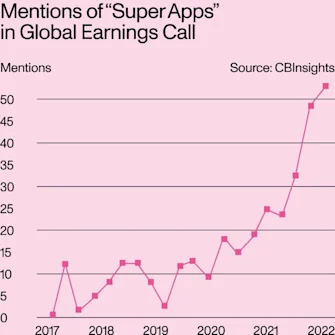

Synonymous with WeChat’s rise is the nebulous concept of the “super app,” which has fascinated business leaders ever since. Since 2018, mentions of super apps in quarterly earnings calls have risen almost 500%, according to market research firm CBInsights.

In April, Uber’s regional boss in the U.K. Jamie Heywood made headlines when he announced the company aims to become “a one-stop-shop for all your travel needs.” In August, the online real estate marketplace Zillow announced its “vision for the housing super app” during a second quarter earnings call. “We have turned the page… to focus our efforts on building a single platform of integrated digital solutions that will serve more customers in our funnel,” said Zillow CEO Rich Barton. His stated objective is to “increase transactions, and to increase revenue per transaction.”

Outside of North America and Europe, the super app has become a cornerstone of corporate strategy and core to the investment thesis for public institutions and venture capitalists alike. Gojek, a Southeast Asian platform with a roughly $30 billion valuation — and a list of investors that includes Meta, Visa, Sequoia Capital and KKR — brands itself on the homepage of its website as “an operating system that unbundles the tyranny of apps.” It can be used for ordering food, setting up prescription delivery, hailing a ride, or booking a massage, and the company has experimented with service lines for everything from house cleaning to salon appointments.

In Kenya, Safaricom and Vodafone’s joint venture M-PESA has over 41 million customers who perform over $300 billion in transactions ranging from money transfers to loans, buying insurance to shopping in stores, and offers functionality similar to Gojek and WeChat by letting businesses create ‘mini-programs’ inside their app to engage directly with consumers. Grab, a Singaporean app that provides food delivery and transportation services in the vein of Uber, has based their entire roadmap on a “super app strategy” as has Yummy in Latin America. In South Korea, the company Yanojla, with business lines ranging from transportation to hotel bookings and cloud computing services, is preparing to go public – turning founder Lee Su-jin, a former janitor, into a billionaire in the process.

Finally, in the realm of reality television, one of the most prominent rationales for acquisition in Elon Musk’s and Twitter’s on-going “will they or won’t they?” soap opera has been the notion of transforming Twitter into a super app. During a panel for the “All-In” podcast in May, Musk said:

“If you're in China, you kind of live on WeChat, it does everything. It's sort of like Twitter, plus Paypal, plus a whole bunch of other things. And all rolled into one … great interface. It's really an excellent app… It could be something new, but I think this thing needs to exist.”

Whether or not you can actually imagine yourself booking at Delta flight, reading a paid newsletter, or paying a friend for dinner through Twitter, the allure the super app has dominated discourse since Blackberry Founder Mike Lazaridis popularized the term, referencing it at his 2010 keynote address at the Mobile World Congress conference in Barcelona.

Scaling the summit

WeChat has had substantial structural advantages. While features to meet new people accelerated initial growth – and popularized the QR code in China – being able to import contacts from the desktop program QQ solved the network effect problem (“if my friends aren’t there, why would I use it?”) commonly faced by new social platforms. The Chinese government’s tight control of online discourse and monitoring of traffic created protectionist advantages for Tencent by blocking foreign competition, including the banning of Facebook in 2009.

“China was a unique place in time when WeChat came up,” notes Emeka Ajene, a Nigerian-based former Uber executive, author of Afridigest, and founder of the transportation platform Gozem. “It’s a bit of a walled garden, and there’s some picking of winners and losers with the government putting their thumb on the scale. It’s very hard to [follow WeChat’s path] and say: okay, I want to start with chat, and I’m going to beat WhatsApp, who’s already there. You’d need a real value proposition.”

But WeChat has also been a beacon of innovation: “Official Accounts,” (OAs) became hubs for business presence, and mini-programs enabled third-parties and software developers to build rich functionality on top of WeChat, including tracking shipments, paying bills, browsing a product catalog, ordering a taxi, looking up account information, or booking reservations.

Compared to the concept of mobile applications today, what WeChat represents can be better understood as an operating system that just happens to live on top of the existing operating system installed on your phone.

In this analogy, WeChat provides some base functionality itself — like Apple’s iTunes, Wallet, or Mail — but the main value is providing the infrastructure for an ecosystem of businesses to build their own functionality (Apple’s developer tools) in hopes of accessing a large base of consumers (Apple’s app store). Mini-programs act as lower-fidelity mobile apps, enabling surprisingly rich functionality, like streaming games or tv shows.

This functionality creates a positive feedback loop: extending the value proposition of WeChat itself, which leads to the acquisition of more users and increased engagement with existing users — which then leads to more engagement by outside businesses on the WeChat platform. WeChat doesn’t need to build itself – it only needs to provide the tools for others to build, because access to its consumers incentivizes others to fill the void.

“A super app allows developers to create use cases that reach beyond the original use of the platform,” says Cliff Kuang, designer and author of the new book User Friendly. “WeChat was a chat app, but it’s all these other things, not because WeChat developed [that functionality] — but because they created a platform where developers can extend the functionality of WeChat and meet users where they are.”

All this begs a question: do you really need a super app? Many of the internet giants – Amazon and Alphabet, Meta and Alibaba, don’t have a single app to rule them all, but rather a tapestry of interconnected, yet differentiated, digital platforms and products. Businesses who focus on one monolithic app, like Snapchat and Bytedance (Douyin in China, TikTok in the the rest of the world), are at best incrementally increasing their ‘suite of services,’ with minor advances in eCommerce shopping, payments, and creator tools.

Are Amazon and Google not “super” because they don’t have a super app? In effect, they are digital conglomerates – the Sears and GE of the 21st century. Do they not claim their cut of all digitally-related economic activity? From cloud services (AWS, GCP) to eCommerce fulfillment (FBA), from hardware (Kindle, Echo, Ring; Nest, Pixel) to digital advertising, to ownership of search (Google), video (YouTube; Twitch & Prime Video), and product discovery (Amazon) — both dominate our digital experience in North America and beyond.

Each operates platforms that cut across content, commerce, and utility in their own unique ways. “There’s less whitespace in the west,” says Ajene. “There’s behemoths in almost every vertical. Markets like Southeast Asia and Latin America and Africa have smaller revenues per user. Plus, there’s fragmentation. There are 54 countries in Africa. They’re very unique. You have to go market by market.” The combination of variation and size of markets requires a different approach. “There are fewer competitors. So you can aggregate users over a bunch of different verticals and extend the lifetime value of that user.”

What a super app like WeChat enables is not just expanding beyond a specific lane like content, commerce, or utility – the latter being the lane that many of the more recent self-declared super apps fall into, especially those starting in transportation or payments – but it also offers a multiplicative increase in services and offerings by enabling first-party, third-party, and consumer to consumer interactions and inventions.

This is the true value proposition of a super app strategy. Not just category expansion, like Uber moving into other forms of transit. Instead, providing the infrastructure upon which a full-fledged, many-sided digital ecosystem is built – and being able to claim a portion of all economic activity.

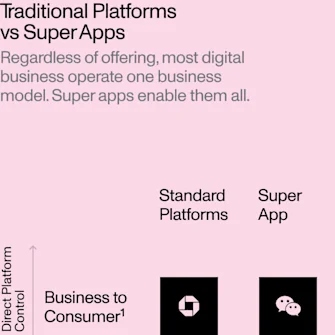

Traditional Platforms vs Super Apps

Regardless of offering , most digital business operate one business model. Super Apps enable them all.

1. Supply (products, services, and content) produced and controlled directly by the platform. 2. A connection of supply (1st or 3rd-party) with demand (users), quality controlled by the platform. 3. A connection of supply (mostly or all 3rd-party) with demand, with minimal quality control. 4. Platforms that enable pure consumer-to-consumer (C2C) exchange and engagement.

The next generation of super apps

In late 2020, Facebook expressed a ‘distributed’ super app strategy, with WhatsApp Chief Operating Officer Matt Idema stating a vision where “Instagram and Facebook are the storefront, [and] WhatsApp is the cash register.” Since then, they’ve consistently explored commerce and marketplace offerings, but in the grand scheme of their earnings, eCommerce has been a rounding error compared to advertising.

If you look closer, there are examples in the West of an “operating system on top of an operating system” that began with a social-and-content orientation, like WeChat, as opposed to a utility like payments or ride-sharing. They’re video games. Roblox and Minecraft offer fully realized creator tools that extend the underlying functionality of both platforms and enable monetization, including billions of dollars in virtual transactions. What began as content evolved into commerce, and for those developing social networks inside the gaming world, it has also become a utility.

In many ways, this appears to be where Meta, née Facebook is heading.

“So much of this is constrained by the initial conditions of why someone is using your app,” says Kuang. “A lot of people realize they don’t necessarily have the license from their users [to become a super app]. Is anybody going to use Uber to plan their next vacation? Second Life was really interesting because people were just hanging out. Maybe Minecraft becomes that. If you miss out on the next computing platform, you miss out on the next 20 years.”

In New York Magazine, the entrepreneur turned author Scott Galloway recently quipped “every time you hear Zuckerberg say metaverse, swap in super app and the plan sounds less stupid.” If the next super apps do lie in the metaverse, Meta’s start has been ominous – they’ve already been criticized for high transaction fees hobbling a nascent creator economy in “Horizon Worlds,” the pre-installed virtual world in their Oculus headset.

While the door for super apps may be closing in two dimensions, the virtual window is just opening in three.

Holden Bale is a Group Vice President and Head of Huge’s Global Commerce Practice.